On July 2, 1913 the Lehigh Valley was in preparation for another glorious, if unsafe, 4th of July celebration. But except for a few folks in South Bethlehem, no one was ready for the exciting news that came out of the White House and was carried on front-pages across the nation. This is how it appeared in the New York Times:

“President and Mrs. Wilson announce from the White House to-night the engagement of their second daughter, Jessie Woodrow, to Francis Bowes Sayre of New York. The wedding which will be the thirteenth in the White House is expected to take place in November. Mr. Sayre is the younger son of the late Robert H. Sayre, the builder of the Lehigh Valley Railroad, who was also the organizer and general manager of the Bethlehem Iron Works, now the Bethlehem Steel Works. The mother of Francis Bowes Sayre was the daughter of John Nevin, President of Franklin and Marshall College at Lancaster, Penna.”

The excitement of a White House wedding swept over the Lehigh Valley. Naturally the press carried all the details that they could. Wilson had visited the Lehigh Valley twice during the 1912 presidential campaign. He carried Allentown and Lehigh County in the election.

Miss Wilson was 24 years old and had been born in Gainesville, Georgia. She had been educated privately at Princeton where her father taught and was later president of the university. She had graduated from Goucher College, had a degree in political science and had recently completed three years of settlement housework.

Mr. Sayre, the press pointed out, had been born in South Bethlehem in 1885. He had spent two years at the Hill School and two at Lawrenceville School. He spent his summers on the Shoshone Indian Reservation in Montana. Sayre went on to Williams College where he was manager of the football team, president of The Good Government Club, headed the Y.M.C.A. Club and was class valedictorian. He spent two years in Labrador with Wilfred Thomson Grenfell, a British medical missionary who would later be Sayre’s best man. In 1909 he entered Harvard Law School and graduated in 1911. He was working as an attorney for the New York District Attorney Charles S. Whitman, a position he got on the recommendation of President Theodore Roosevelt, a former New York city police commissioner. On hearing the news Whitman was asked to comment. “Mr. Sayre is a man of a great deal of ability, and I have grown very fond of him in the year he has been working for me. It is a pleasure to me to learn of his engagement to the President’s daughter. He is to be congratulated and certainly his fiancée has every reason to be proud of him.”

Francis B. Sayre

Sayre notes in his memoir Glad Adventure he had gotten to know the Wilsons through his mother’s sister Blanche Nevin, known in the family as “Aunty Blanche,” who was a sculptor. She had met them in 1910 while vacationing in Bermuda and did a bust of Wilson that is now in the Capitol Building. Sayre met Jessie for the first at his aunt’s home, “Windsor Forges,” a colonial era dwelling at Churchtown, Lancaster County, where she lived when not in Europe. An ancestor had run the Forge in the early 19th century. Sayre was on his spring break from Harvard Law School. He and Jessie “walked over the country roads, drove up to Lancaster one day and there saw Buffalos Bill’s Wild West Show, undercover in a torrent of rain,” Sayre recalled.

In October of 1912 Sayre was seeing Jessie regularly at her family’s home in Princeton. It was under the colorful autumn foliage as they “drove behind a very understanding horse” that Sayre proposed. Jessie asked for time to think it over. The following Tuesday he stopped again to see her. As Sayre described it, “Jessie met me at the door then she threw her gray cloak about her, and led the way into the foggy street, then without a word she raised her face to mine and put herself into my arms.” Apparently, that was a yes. Jessie did not break the news to her father until he won the election. At the time of the wedding announcement, Jessie was a guest of Sayre’s mother at Lancaster.

Many people could recall the last wedding at the White House in 1906 between President Theodore Roosevelt’s outspoken daughter, Alice, and Nicholas Longworth. In letters to his mother, White House chief of protocol, Roosevelt family friend and Titanic victim Archibald Butt noted seeing Alice driving around Washington in her Baker Electric automobile. Butt got a kick out her antics. Others did not. Alice shocked official Washington by such indecorous behavior. When approached by someone who suggested he should control his daughter, Roosevelt replied, “I can either run the country or I can control Alice. I cannot possibly do both.”

Guests at Francis B. Sayre wedding

Longworth’s marriage with Alice became strained when he supported Taft over her father in the 1912 presidential election. He later became Speaker of the House, but they were never close after 1912. In her later years Alice Roosevelt is said to have had a pillow with the words, “If you don’t have anything nice to say sit by me” embroidered on it.

Although no Alice Roosevelt, Jessie Wilson was no shrinking violet either. She had supported her father in his tumultuous campaign that had split the Republican party between incumbent President Taft and former president Roosevelt which many historians believe opened a way for Wilson to win the election. The country was barely getting used to Wilson who had only been in office for four months. Although a part of what was then thought of as the Progressive wing of the Democratic party, growing up in the south Wilson shared many of the views of white Americans on both sides of the Mason-Dixon line about race.

In the 1950s and early 60s historians tended to judge Wilson as a liberal icon because of his heroic but failed attempt to get the U.S. to join the League of Nations, the establishment of the Federal Reserve system and his leadership of the nation during World War I. A 1948 and 1962 poll of historians conducted by historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. listed Wilson as a great or near great president. Today historical opinion on Wilson is divided. While not denying his significant historic role, it views his firing of Black government employees, establishing restrictions making it more difficult for Black people to find civil service jobs, and his refusal even to discuss the issue of civil rights as racial discrimination. Wilson’s showing at the White House of the technically brilliant but blatantly racist D. W. Griffith film “Birth of a Nation” in 1915, the first film shown there, seemed to confirm this in some minds. Even at that time it caused such outrage that it eventually forced Wilson to issue a statement denouncing the film.

On June 26, 2020, the Woodrow Wilson School of International Affairs Board of Trustees voted to change its name to the Princeton School of International and Public Affairs due to protests by students and faculty over Wilson’s “racist thinking and policies,” thus making him “an inappropriate namesake for the school.” When other issues like federal regulation of child labor or support of a constitutional amendment for women’s suffrage came up, Wilson said they were state issues that voters of those states should decide what they wanted without federal interference.

There was no dispute over the White House wedding plans that were drawing attention from across the nation. The wedding day, November 25, 1913, in Washington dawned clear with only a few fleecy clouds. Although it was late November the air was warm enough to have been that of early October. One observer called it perfect Indian summer weather.

Jessie Wilson

A crowd had begun to gather around the front gate of the White House. About 70 police were out front but the generally peaceful crowd left them little to do. There were exclamations of awe as elegant chauffeur-driven cars arrived at the entrance. But not all were so lucky. Many who arrived later came, according to one observer, in “pedestrian taxicabs.” Sayre himself had trouble being admitted to the White House when a police officer refused to believe he was the groom. It was only after an appeal to a police captain that he and his best man were allowed in.

Inside the Marine Band, resplendent in red coats and gold braid, waited. Some of the first guests to arrive were members of the House of Representatives. The legislators had already given their gift to the bride in the form of a diamond pendent with small diamonds around it. The press would later note that Jessie Wilson was wearing it on her wedding dress. It was among the many gifts the couple had received. A newspaper article of November 17 noted that 5 sterling silver tea sets had already arrived. Sterling silver dinnerware was another fallback present for those who could not think of anything else. The press covered in detail the dresses worn by the women at the wedding right down to the lace fringe.

The full diplomatic corps, some in uniform, were present. The German ambassador Count von Bernstorff was far from the stereotype of an arrogant Prussian. He played golf with the men and was an excellent hand at bridge. Invitations to play a “rubber” of the game at his home were said to be coveted by social Washingtonians. Heading the delegation was Jean Jules Jusserand, the French ambassador and dean of the diplomatic corps. He was a longtime fixture in Washington. During one of Theodore Roosevelt’s so called “stunts” he had joined the president and some staff members for a dip in the buff in the Potomac. Jusserand, however, retained his white gloves, as he said later, “in case we should meet some ladies.” At least three of the nations represented at the wedding, Kaiser Wilhelm’s Germany, Franz Joseph’s Austria-Hungary, and Czar Nicholas II’s Russia would, in less than a year, find themselves locked in World War I and be swept away in the war’s wake.

The service was to be conducted by Rev. Dr. Sylvester Beach, pastor of Princeton’s First Presbyterian Church where the Wilson family worshiped. In 1919 his daughter Sylvia Beach opened the famous Shakespeare and Company bookstore in Paris where in the 1920s and 30s she would champion avant-garde writers like James Joyce and Gertrude Stein. With Rev. Beach was Rev John Nevin Sayre, an Episcopal priest who was the groom’s brother. He had rushed home from China to take part in the wedding. A combination of the Presbyterian and Episcopal marriage services had been created for the wedding.

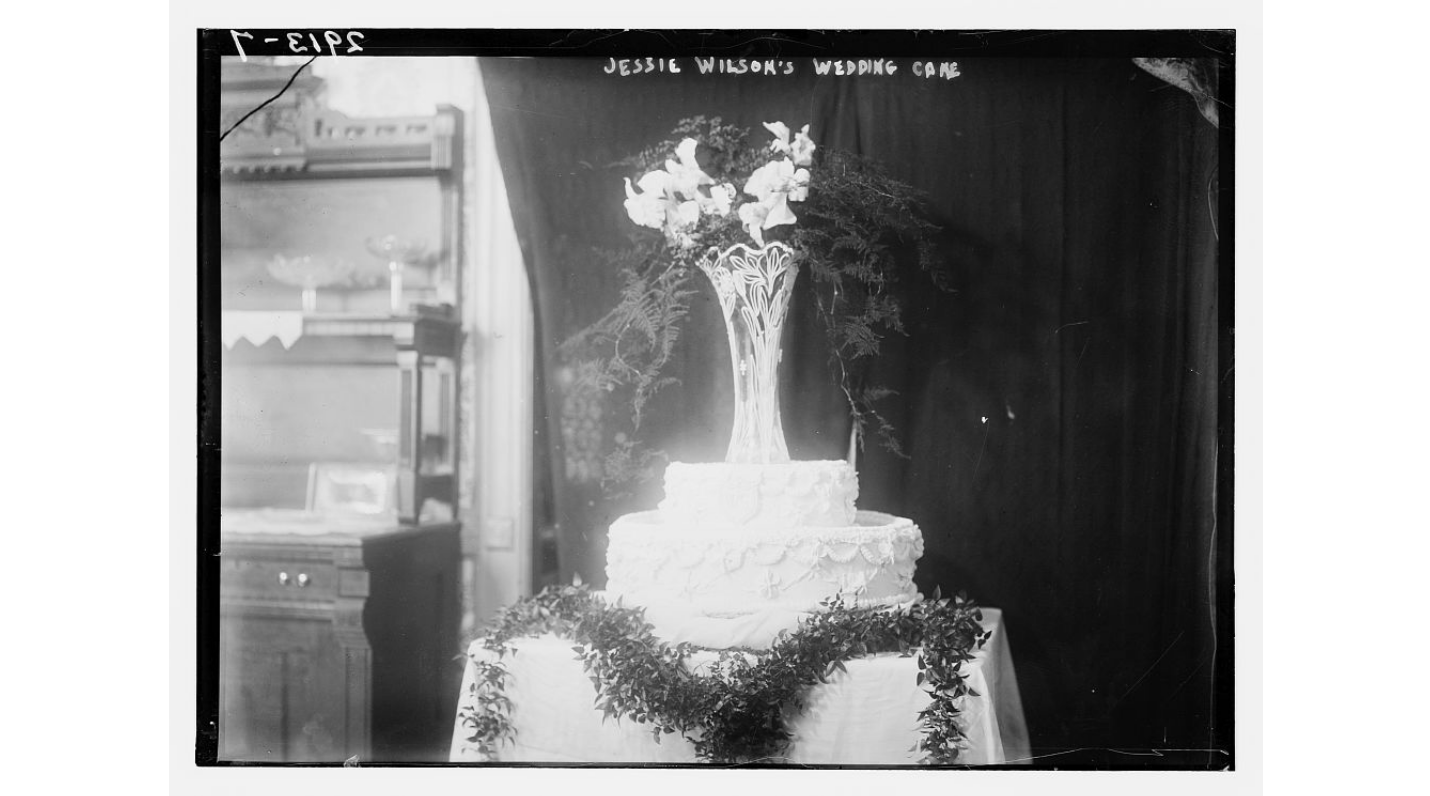

Jessie Wilson’s wedding cake

The guests were divided into three sections as ushers in swallow-tail coats and pearl grey trousers escorted the various dignitaries to their seats. Two guests who were conspicuous by their absence, Vice President Thomas R. Marshall and his wife, were on a trip to the southwest. Wilson had needed Marshall to swing the voters of Indiana to him in the election, but the stiff, formal Wilson and the easygoing, joke-telling Marshall would have a split that ended up with Wilson exiling Marshall from the White House.

Finally, all was ready. Music began to play as Mrs. Wilson and Mrs. Sayre, the respective mothers of the bride and groom were shown to their places. Then President Wilson and his daughter entered to the Marine Band playing the well-known wedding march from Lohengrin by Wagner.

Sayre was waiting, standing on a vicuna rug presented to them by the minister from Peru. The ushers were on the right and the bridesmaids on the left. Here is how the press described the scene:

“As the two pledged their troth, the President and Mrs. Wilson stood to the left, hand in hand on the platform. ‘Who giveth this woman to be married to this man?’ asked the Rev. Dr. Beach. The President stepped forward, took the hand of his daughter, and placed it in the hand of Mr. Sayre. ‘I, Franklin Sayre, take thee, Jessie Woodrow, to be my wedded wife,’ repeated the bridegroom after Dr. Beach, ‘and promise and covenant before God and these witnesses to be thy loving faithful husband, in plenty and in want, in joy and sorrow, in sickness and in health as long as we both shall live.’ The bride then repeated the vows. It was at her request that the word ‘obedient’ be added to her vows.”

The reception was held in the Blue Room. Here the couple with President Wilson and his wife greeted the guests. During the reception refreshments were served in the state dining room. Many of the guests were old friends of Sayre’s from Williams College. A surprise guest was Rear Admiral Robert Peary the Arctic explorer with his wife. “They were accompanied by their daughter (Marie Ahnighito) born within the Arctic Circle and known the world over as ‘the snow baby.’ She is now a young Miss of Twenty,” noted the New York Times.

A “southern” supper followed in the breakfast room. Although dancing had not been planned perhaps at the couple’s request the East Room was cleared, the Marine Band called in, and “one of the most delightful parts of the affair,” was held. “The young people footed it merrily to the strains of the tango and other up-to date dance music, ” noted the Times.

The couple left at 8:00 that evening for their honeymoon to points unknown but they were overheard telling friends they would see them at the Army-Navy Football Game. In fact, the Army-Navy game that year was held at New York’s Polo Grounds on November 29, the day the couple went on a tour of Europe. They went to a house in Baltimore provided by a friend where they could be alone. The North German Lloyd liner George Washington, known for its comfort and luxury rather than its speed, had been chosen for the crossing. One of the Washington’s four “imperial” suites was occupied by the couple. Its captain had set aside a special gangplank covered with red, white, and blue bunting. Photographers and reporters from all the New York papers were waiting. When President Wilson appeared, he lifted his bowler hat and photos were taken, but where were the newlyweds? Finally, as Wilson was talking to the ship’s captain, he heard Francis Sayre’s voice behind him say, “here we are.” Sayre explained later that he and Jessie had taken “the tube” from New York to Hoboken, N. J. and then a horse cab to the pier. They then walked on to the ship on the regular third-class ramp. Wilson laughed loudly and then they walked over to the waiting press.

Shortly later the president left to attend the Army-Navy game. The next time he would be on the deck of the George Washington would be in 1918 after it had been confiscated as enemy property by the U.S. government and carried him to and from France for the Versailles Peace Conference, officially ending World War I.

The Sayres spent most of their time in Europe in London and Paris. Here they met many of the prominent people of the day. When the couple returned to America, Francis Sayre took up a position as assistant to the president of Williams College. The couple were to have three children. Francis B. Sayre (1915-2008) was later Dean of the National Cathedral in Washington and an outspoken supporter of liberal causes including civil rights and anti-Vietnam War protests. His sister Eleanor Axton Sayre was born in 1916 and was later an expert on the h 18th century Spanish artist Goya. Her brother Woodrow Wilson Sayre was born in 1919 became a philosophy professor and mountain climber.

The couple were in Southeast Asia in February of 1924 when Woodrow Wilson died. Later Jessie Woodrow Sayre took an active role in Democratic Party politics in the 1920s, turning down an offer to run for the U.S. Senate. She died on January 15,1933 at the age of 45 following abdominal surgery in Cambridge Hospital because of either a gall bladder disorder or an emergency appendectomy. On January 19, 1933, she was buried in the Sayre family plot at Nisky Hill Cemetery in Bethlehem. Her brother-in-law the Rev. John Nevin Sayre conducted the services. Her husband was devastated and by his own admission in his memoir went through a spiritual crisis over it for a time.

Sayre, whose work in international law particularly in Southeast Asia in what is now Thailand, was praised for his skill in handling trade negotiations. He remarried in 1937 to Elizabeth Evans Graves, widow of Ralph Graves of the National Geographic Society. He also served as an assistant Secretary of State for trade.

In 1942 Sayre was evacuated by a submarine carrying 20 million dollars of the gold reserve from the Philippines where he was serving as U.S. High Commissioner following the invasion of those islands in World War II. He held numerous other high level government positions until his death in 1972. Francis Sayre is buried at the Washington National Cathedral.